MODERSOHN-BECKER

“Who was Paula Modersohn-Becker? Why had I never heard anything about her?”

—Marie Darrieussecq

LE MONDE

Moderne / Blog abonné

April 9, 2016 by Stéphane Guégan

“Cher Guy . . .”

“Le livre de Diane Radycki, livre d’une rare intelligence…”

Art Review

February 26, 2016 by Roberta Smith

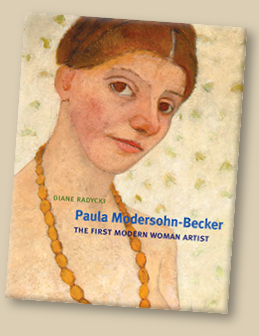

“A Painter Before Her Time”

“The St. Etienne show . . . affirms Modersohn-Becker as ‘The First Modern Woman Artist,’ which is the subtitle of Diane Radycki’s compelling 2013 monograph on her life and work.”

Page-Turner

October 30, 2013 by John Colapinto

“Paula Modersohn-Becker: Modern Painting’s Missing Piece”

“Radycki performs some sharp detective work to suggest that Picasso’s knowledge of a 1906 Modersohn-Becker portrait played a crucial role in his solving the problem, later that same year, of how to paint the head in his seminal portrait of Gertrude Stein—just one piece of evidence that allows Radycki to call Modersohn-Becker’s story ‘the missing piece in the history of twentieth-century modernism.’”

HUFFINGTON POST

Featured article on Huffpost Arts & Culture

October 20, 2013 by Marcia G. Yerman

“Paula Modersohn-Becker: The First Modern Woman Artist . . . relates the personal story and artistic history of a woman that has much to offer today’s audiences. Radycki’s book, which had its origins in a Harvard Ph.D. dissertation, sees Modersohn-Becker as a pioneer and groundbreaker who was trying to navigate ‘having it all.’”

LONDON REVIEW OF BOOKS

August 8, 2013 by Mary Ann Caws

“The Artist as Fruit”

“I loved reviewing your book.” MAC to the author, August 30, 2013

LE MONDE

Moderne / Blog abonné

April 10, 2013 by Stéphane Guégan (curator, Musée d’Orsay)

“Paula B., l’imp®udente”

“Paula B., Taking Risks”

For two decades now, research inspired by feminism has been elevating Paula Becker to the ranks of the most significant of women artists—an equal of Frida Kahlo and Cindy Sherman.

It is true that she painted the first representations of a mother nude and of adolescents nude, images never before realized by a woman. This friend of Rilke was not afraid to take risks.

Her greatest claim to posthumous glory is, in my opinion, her self-portrait of 1906, which shows her half-dressed, like a Tahitian by Gauguin—one hand under her breasts, the other under her round belly—smiling at her own nudity, at the chance of carrying a child, happy too about what she is provoking in the gaze of others. Because otherness here arises not from an exoticism, not from an elsewhere, which would justify the rejection of social conventions. This ground-breaking painting was painted by Paula Becker in Paris, in the Paris of Picasso and of Rilke, two figures in her circle. No, this otherness is based on her awareness of a difference and of a status that the artist intended to make recognizable through her painting and by herself alone. As Diane Radycki, the best expert on the artist, goes on to elucidate, this painting goes beyond the context of a head-on rivalry with the Rose-period Picasso and his archaic turn in Gósol. The choice to represent herself pregnant, even though in reality Paula was not, allied her desire to be a mother with several icons in the Louvre with which she had spent much time, from the Venus de Milo to the Venus of Cranach. To give shape to the idea of fertility is one thing, to give it this meaning is another.

It is necessary to pay attention to the inscription she wrote at the bottom of the painting: “I painted this at age 30, on the occasion of my 5th wedding anniversary.” Such an affirmation, in the first person, has a double meaning—one for the artist and one for the woman—the first pushing the second to break up her marriage with the landscape painter Otto Modersohn. There is defiance in this belly and this dilated navel, which Diane Radycki connects to the portrait of the Arnolfinis by van Eyck and the celebrated photograph by Annie Leibowitz of Demi Moore pregnant, on the cover of Vanity Fair.

By projecting herself into an uncertain future, Paula Becker also made an assessment of her career launched fifteen years earlier. Child of a bourgeois Dresden family, and having benefitted from an excellent education and an international training in art, the young woman had no taste for the bohemian life of squalor. The arts community of Worpswede, just outside Bremen—where she first met Otto Modersohn in 1897—requires, on the contrary, a life of exemplary probity, of which being moored in the country is a sign. Paula Becker could have settled in with its landscape artists, gently rustic and not at all modern. The first break: she left Germany, alone, the 1st of January 1900. This first stay in Paris lasted six months, which was spent between the Academy Colarossi, the Ecole des Beaux-Arts (where women had been accepted only a short time before), and the Louvre.

Her paintings from this period show her interest in Cézanne, Gaugin, Degas, and van Gogh, figures in the modern pantheon. Paris had, above all, to give her the mastery of the human figure to which she aspired, as she wrote in her letters.

Three more stays followed which punctuated her modest career in Germany and the strange life as a couple that she shared with Otto Modersohn. She had married this austere man after the death of his first wife. But it seems that this marriage remained unconsummated until 1906. In the meantime, Paula, following the example of Picasso, had taken in the primitivism of Gaugin and the advances of van Gogh.

At the time of her premature death in November 1907, less than three weeks after giving birth to a little girl, recognition of the painter was still to come. It did. In 1927 a museum named after her opened in Bremen. Woman and modern, she would not escape, ten years later, the honor of inclusion in the Nazis’ great exhibition of degenerate art. Her renown today is only greater and more certain because of it.

(translation by Victoria Schlegel and Diane Radycki)

HUFFINGTON POST

15 Best Art Books This April

April 4, 2013

“Paula Modersohn-Becker was one ballsy lady. She was the first woman to paint herself nude. . . . If that doesn’t make her a pioneering woman artist, we don’t know what does.”

BOOKSLUT

Book of the Week

March 26, 2013 by Jessa Crispin

An Interview with Diane Radycki

“Diane Radycki’s Paula Modersohn-Becker explores [the] pressures on the female artist’s life at the turn of the century, and the way modernism has been defined as masculine. She also brings Modersohn-Becker more fully to life, adding a darker tone to the relentlessly cheerful letters she sent home to worried parents. And the paintings and sketches are all beautifully reproduced, introducing us all to this important and beautiful painter.”