MODERSOHN-BECKER

AT THE THRESHOLD OF MODERNISM Paula Modersohn-Becker risked everything in order to become “something.” Who she became was a daring innovator of gender imagery—the first modern woman artist to challenge centuries of traditional representations of the female body in art.

Before Modersohn-Becker (1876–1907), no woman artist painted herself nude, or mothers nude, or girls nude. Not only did she reconfigure the nude, but she also resituated still-life painting. She arranged it in the kitchen as a site of domestic practice and the tasks of meal preparation. Given her originality, her long friendship with the great lyric poet Rainer Maria Rilke, and her reputation among contemporary artists (Jenny Holzer, Mother and Child, for Paula Modersohn-Becker, 2005), it is surprising that she is not better known in the United States.

One reason may be her untimely death. In 1907, not long after painting her revolutionary nudes and giving birth to her first and only child, Modersohn-Becker died, age thirty-one, unknown, and ahead of her time. There would be no more of her work to put in perspective pictures never before seen. Another reason may be that until recently only part of her story was available. Even for those who know her work well, her artistic struggles and personal anguish—years in an unconsummated marriage, racking irresolution about motherhood, a disappointing affair, ongoing financial difficulties, and vulnerable isolation—come as a surprise.

It has taken the popularity of Frida Kahlo, the rise of Cindy Sherman, and a century of women artists whose works confront sexuality, culture, and artistic tradition (Hannah Wilke, Ana Mendieta, Rosemarie Trockel, Rineke Dijkstra, and VALIE EXPORT, among others) to recognize fully what Modersohn-Becker pioneered. The time is here for a new look at this groundbreaking artist.

This book transcends the standard biographical approach by reaching out from her short life to her posthumous fame. It features biography and picture analysis, maps her exhibition history through World War I, the Weimar Republic, the 1937 Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition—and makes an important contribution to understanding the significant role of women artists in the complex revolution of modernism.

This slightly unconventional monograph of a highly unconventional artist is organized in four parts: the beginning; the middle; the work; and the end. To tell this story I draw substantially upon primary sources. A riveting sequence of first-person accounts, which opens the chapter on portraiture, reveals the personal cost when one woman genius wants it all—a big career and motherhood—in an era before women had the vote.

Throughout I look at various artistic, social, and political milieus—especially in Dresden and Bremen—that in a new century were giving rise to the Neue Frau (New Woman), as well as the new woman artist. I analyze the formal skills and habits that were formed by Modersohn-Becker’s different art school experiences in London, Berlin, Worpswede, and Paris. She went to Paris three times before moving there in 1906, each time with a different intention. These three Paris trips are surveyed in one chapter, as learning experiences that grew out of each other. The first, made when she was single, lasted six and a half months; the next two, taken after she married, were for five and eight weeks, respectively. In order to understand her artistic project, I analyze each of her genres: landscape, still life, and figure—paying particular attention to the nude. In an attempt to catch the beat of her moment in a turning century, I employ a prose that mixes the modern with a time-honored vocabulary. Finally, to forefront the long-term consequences of the risks Modersohn-Becker was taking by being so far ahead of the curve, I interrupt the biography twice, with chapters that jump-cut to her pre- and post–World War I fame, respectively.

The book is plotted visually as well. Part 1 starts with artifacts: a gallery of photographs and images of the first books about her; Part 2 is mostly black-and-white, as we watch her learn her craft and encounter French art, that is until she sees—in an explosion of color—Cézanne, Degas, Gauguin, and van Gogh. Color for her own work is introduced in a short sequence at the end of Chapter 5 when she begins painting on her own terms. After that, in Parts 3 and 4, her work is illustrated in color—until the penultimate chapter, which is set in the 1920s and tracks the responses of the postwar art world to her prewar artwork. The last chapter ends her life and, with the exception of paintings lost in World War II, ends it in color.

As for the text, Part 1, “Beginning and End,” presents two families: one the biological family that raised Paula Becker, and the other a circle with elective affinities that, after her untimely death, promoted her work. Her ancestry is bourgeois (Becker) and noble (von Bültzingslöwen), somewhat troubled and somewhat adventurous. (A horrific death that Paula witnessed when she was a child marked her “first glimmer of self-awareness” and her artistic imagination.) The other “family”—artists, gallerists, museum directors, and collectors—furthered her reputation posthumously in print and in exhibition.

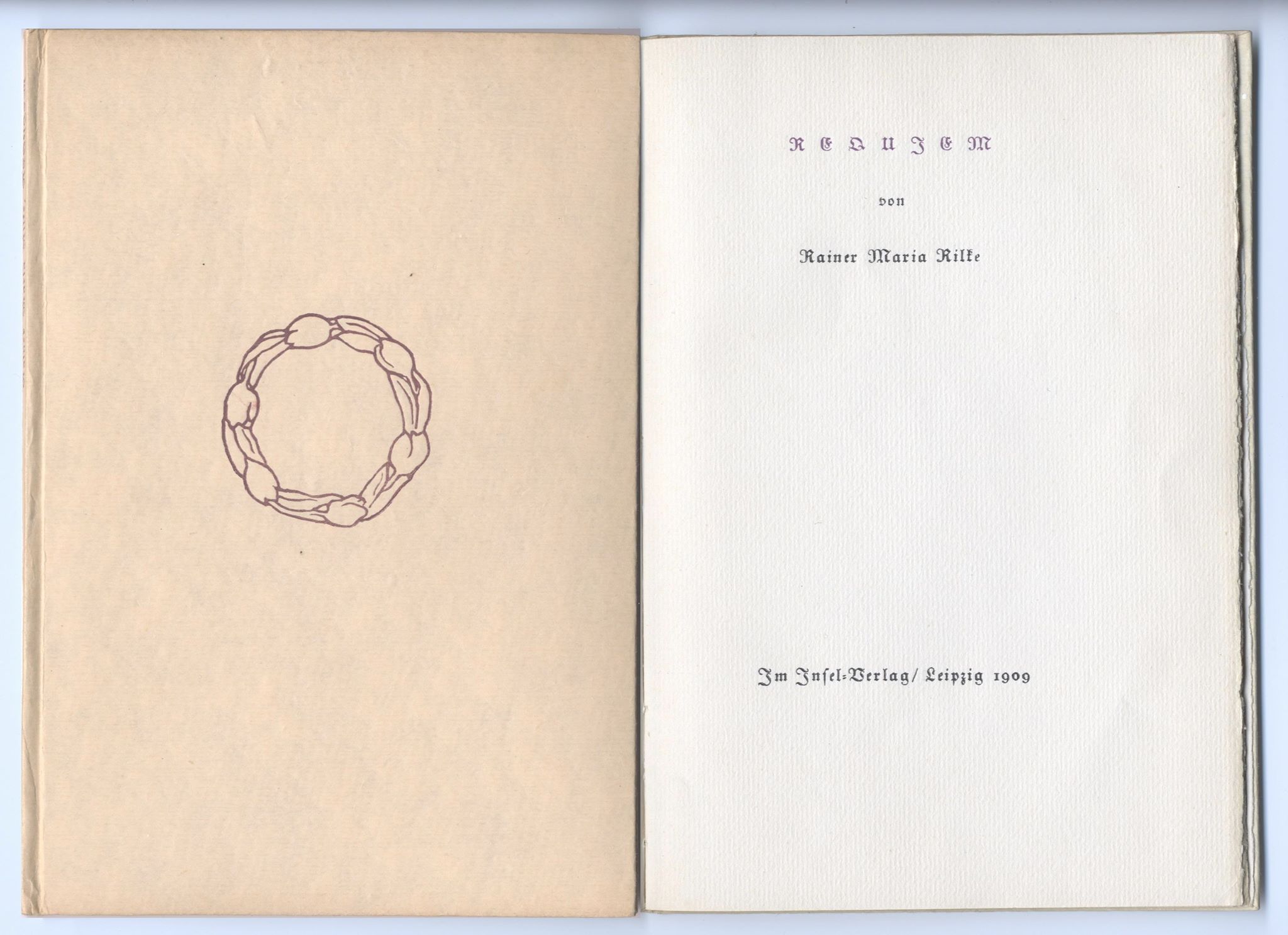

Within a year of her death in 1907, Rilke wrote his moving Requiem for a Friend. In 1911 the first feature article appeared in the feminist literary monthly Frauen-Zukunft (Women Tomorrow) (among its contributors were Thomas Mann, Lou Andreas Salomé, and George Bernard Shaw). But it was not until after World War I that Modersohn-Becker attracted a large and loyal readership, specifically with the publication of her letters and journals. Meanwhile, memorial exhibitions of her work, which were organized by friends as early as 1908, moved on from local venues to galleries, art fairs, and exhibition spaces throughout Germany—and made contradictory claims about her art. Nineteenth-century or modern? Provincial or international? Juvenile or genius? A favorite daughter or a great artist?

Paula Becker and Clara Westhoff, in Becker’s studio, Worpswede, 1899.

Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Bremen.

Part 2, “Mittel (Middle, Means, Medium),” begins answering these questions by returning the reader to her life story. Paula Becker grew up in a rapidly modernizing Dresden and in the historically independent Hansa city of Bremen; she trained at professional art schools in London (coeducational) and Berlin (girls only), and privately in Worpswede. Thereafter, she was back and forth between Worpswede and Paris, between a rural art colony on the north German moors and the teeming capital of the avant-garde with its competitive heat. This was a period of close friendships with the sculptor Clara Westhoff and with Rilke (who were married), and of courtship and marriage to the landscape painter Otto Modersohn. Eleven years her senior and a recent widower with a two-year-old daughter, Modersohn was a founder of the Worpswede art colony. He was also, she was soon to discover, threatened by the art scene in Paris.

Part 3, “I Painted This,” details the risks Modersohn-Becker took. Rapidly absorbing Cézanne, Degas, Gauguin, and van Gogh, she defied expectations, explored imagery, scrambled genres, and ran the course of all young Turks in Paris in the early twentieth century. For models the painter chose unlikely females—those without fashion or sexual currency—the young and the old. Under her brush, blood-and-soil peasants were the bodies of existential awareness. “She was,” her husband admitted, “understood—by no one.”

At age thirty—her self-imposed deadline for “becoming something”—Modersohn-Becker experienced a crisis. Stifled in the art colony and frustrated by five years in an unconsummated marriage, the artist had a brief affair and then fled to Paris in the dead of a cold February night, without a word to anyone but the Rilkes (although she did consult a lawyer about divorce). The mounting tension is documented in a succession of iconic portraits: the best friend; the poet-confidante; the electrifying advocate of free love; the judgmental younger sister; the liberating new model; and, not least of all, herself nude, goddess and creatrix. Once settled in Paris, she forsook her married name and painted feverishly, while simultaneously weighing her options for single motherhood. Through Rilke, who at the time was Auguste Rodin’s secretary, she was crisscrossing paths with radical thinkers and artists, Pablo Picasso among them. She had her eye on the Salon des Indépendants and on the careers of other women artists, particularly Berthe Morisot.

Modersohn-Becker, Self-Portrait, Age 30, 6th Wedding Day, 1906.

Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum, Bremen.

Modersohn-Becker painted the life she was living as a woman and artist. She experimented with her medium and her working methods, and photographed herself nude, bust and full figure. The breakthrough came when she transformed the genre of the nude. Over a century later, it remains startling, even shocking, to see paintings of mothers and self-portraits as full frontal nudes. Her majestic and monumental Reclining Mother-and-Child Nude is the body of maternity mapped onto the bodies of fecundity and spectacle. Her manifesto, Self-Portrait, Age 30, 6th Wedding Day, is the nude body of the woman artist as subject and object. A life-size, full-length portrait of herself nude, it is as astonishing today as it was when she painted it in 1906. Modern female body imagery begins here, with Modersohn-Becker. Its next famous practitioner, Frida Kahlo, was not born until the year Modersohn-Becker died.

Part 4, “Beginning and End Continued,” parallels Part 1 and concludes her story twice: first, with the end of claims on her work as unfinished and provincial, even as she continued to elude categorization; and, second, with the end of her mortal life. Whereas for the pre–World War I art world her painting was puzzling and divisive, in the postwar tumult of the Weimar era—of mavericks, iconoclasts, and social critics, as well as of German women’s enfranchisement—her work looked stunningly prescient. She was taken up in 1919 by two astute dealers on the postwar scene in Berlin and Düsseldorf—the young J. B. Neumann and the seasoned Alfred Flechtheim—and from that point her fame grew steadily. In Bremen the Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum, the first museum devoted to a woman artist, opened in 1927. Neumann and Flechtheim brought her to the attention of Alfred H. Barr Jr. and the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1931. Paris and London followed next.

In Germany, however, the avant-garde was finished. As proof, in 1937 the National Socialists organized their massive exhibition of banned modern art, which held up for derision, among others, Marc Chagall, Wassily Kandinsky, E. L. Kirchner, Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka, Franz Marc, Piet Mondrian, and Modersohn-Becker, a rare woman in the temple of degenerates. The Führer was infuriated not only by her transgressive imagery, but also by the claim, carved in stone at the entrance to the Modersohn-Becker Museum, of a woman artist’s immortality.

The final chapter returns to the last year of her life and the dark side of independence: identity crises, poverty, and isolation. After six months of anxious highs and lows, as well as relentless pressure exerted by family and friends, the impecunious Modersohn-Becker agreed to let her importuning husband join her in Paris. She became pregnant and they returned to Worpswede, where she painted the first self-portrait pregnant in the history of art. The woman artist looks straight out at the viewer and brandishes her twin flowers of creativity and procreativity. Deal with it, she challenges us. She died three weeks after giving birth, from complications that arose from the pregnancy.

The artist who died in 1907 had a different story after her death than she has today. By 1936 The Letters and Journals of Paula Modersohn-Beckerhad introduced well over forty-five thousand German book buyers to a charming daughter, wife, artist, and mother—indeed, so relentlessly charming was her story that Rilke argued against its publication. As he explained to her family, he and his wife found the personal and artistic struggles of their friend missing in the writings selected for the general public. Lost for generations to come would be the First Modern Woman Artist, the story that is told here. This story is the missing piece in the history of twentieth-century modernism.